Medieval contraception – a hit and miss affair.

How effective were medieval methods of contraception, when practised by women, to limit the number of unwanted pregnancies? How widely were such methods used? What more appropriate subject to celebrate the first month of the release of The King’s Concubine, a novel of Alice Perrers, in the USA?

And what better way to celebrate than an international Giveaway of two signed copies of The Kings’ Concubine? Leave a comment at the end of the post to put your name into the Giveaway draw.

The primary role of royal and aristocratic brides throughout the Middle Ages – and through much of history – was to produce children as quickly as possible – particularly sons – as heirs to the inheritance. And there was obviously pressure on a wife to produce more than one child since death struck indiscriminately at infants of all ranks. Large royal families were seen as a symbol of dynastic success and future, long-standing authority. The royal brides and mistresses I have written about all produced large families, whatever the drain on their health, which must have been considerable.

Philippa of Hainault, wife of Edward III, gave birth to at least 12 chidren, not all reaching maturity, but a remarkable number grew to adulthood, to marry and have their own families.

Joanof Kent, wife of Edward of Woodstock, the Black Prince, had 5 children by her first husband, and a further 2 sons with Prince Edward.

Elizabeth Plantagenet, younger daughter of John of Gaunt, carried 5 children for the Earl of Exeter, and 2 for her last husband Sir John Cornwall.

Katherine Swynford had at least 3 children by Sir Hugh Swynford, and then carried 4 illegitimate Beaufort children to John of Gaunt.

Alice Perrers, Edward III’s mistress, gave birth to at least 4 children, one of them recognised officially as a son of Edward III, the paternity of the rest more unclear.

And a hundred years later, Katherine de Valois, when wife of Owen Tudor, gave birth to probably 5 children in 6 years.

Was this by choice, to allow pregnancy to follow pregnancy? I would presume it to be in the interests of such intelligent and capable women, and particularly royal mistresses such as Alice Perrers and Katherine Swynford, to limit the number of pregnancies, in spite of the male-dominated church preaching that to inhibit the procreation of children was a sin. So did they practice contraception?

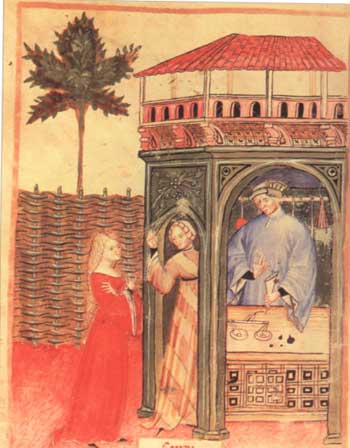

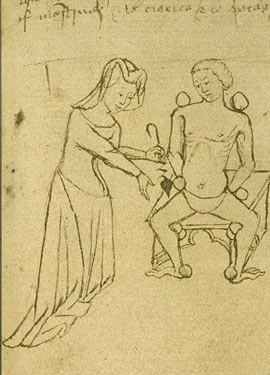

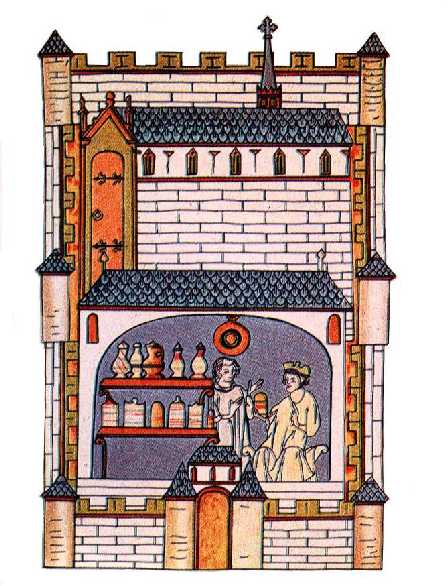

There is no doubt that advice on contraception was available and it was practised by medieval women. The methods were a mixture of amulets, herbal concoctions and old wives’ remedies. The Trotula texts, proported to be the advice of Trotula, a mysterious woman thought to be living and working in the eleventh or twelfth century in Salerno, give us such a wealth of information, allowing us to see into the minds of medieval women. It is clear that there was a demand for remedies against an unwanted pregnancy, and there were certainly women practising as doctors in the Middle Ages, as shown in this medieval manuscript.

Here are 4 tried and tested remedies from the Trotula Texts.

1. Carry the womb of a goat which has never had offspring against your naked flesh. You will not conceive.

2. Remove the testicles from a male weasel before releasing it alive. Carry the testicles in your bosom tied in a goose skin.

3. Hold – or even taste – a piece of jet. Very efficacious!

4. After a difficult pregnancy, place into the afterbirth as many grains of caper spurge or barley as the number of yours you wish to remain barren. If you wish to remain barren forever, throw in a handful.

All, of course, unlikely to have any degree of efficacy. If our royal brides and mistresses attempted any of these methods, we cannot be surprised that they were spectacularly unsuccessful.

Yet it is on record that medieval wives practiced contraception successfully. Clemence of Burgundy, wife of Count Robert II of Flanders in the twelfth century, gave birth to 3 sons in 3 years. After that she practised ‘womanly arts’ because she feared if more sons were born they would fight amongth themselves for their inheritance. Clemence of Burgundy seems to have been successful in the control of her further pregnancies. But what about the women of the English fourteenth century royal court? It is certainly a lesson that Phlippa of Hainault might have learned, for her clutch of healthy sons certainly helped to destabilize England in the coming century.

A method which would appear to have at least some chance of success, first noted in Roman times and advised by Soranus of Ephesus, was the use of a vaginal suppository made from wool, steeped in some gummy substances such as cedar oil or Gum Arabic to limit the liveliness of the sperm. If this did not work, a sneeze at the optimum moment of ejaculation might deter the sperm. One would not hold out much hope.

A far more effective method, and one undoubtedly used, was the practice of abortion by ‘Provoking the Menses.’ A strong menstrual flow was considered in the Trotula Texts to be good for female health, but to encourage it would also bring about a miscarriage and thus an abortion. Herbal concoctions were widely used: red willow root cooked in wine, strained and drunk; a mixture of madder and marsh mallow, mixed with barley flour and white of eggs, made into little wafers; vervain and rue cooked with bacon and eaten. Some herbs were particulalry effecive in ecnouraging the menstrual flow such as fennel.

So what can we conclude about our royal wives and mistresses? Very little in effect, other than that the methods prescribed were ineffective at best and dangerous at worst. Some herbal remedies could be life threatening. Life in medieval times was difficult for women, both rich and poor, pregnancy taking its toll on their bodies and health. We have no evidence that Queen Philippa and her contemporaries ever made use of contraception, but that does not prove that they did not. We are unlikely to ever know the truth of it. What we do have is proof that Philippa of Hainault loved all her children dearly.

Interestingly, on a different slant, the Trotula Texts at least recognised the existance of female physical desire, by offering remedies for women who had reason to deny their sensuality or those not permitted to enjoy intimacy with a man, such as those bound by vow, by religion or by their being widows.

One such recommendation was to anoint the vagina with penny royal oil, which would dissipate the desire for a man and dull the pain. This would at least seem more pleasant, if no more effective, than the Roman Pliny’s advice to apply mouse dung in the form of a liniment. Or secreting the testicles and blood of a dunghill cock under the bed. Or, if a woman’s loins were rubbed with the blood taken for the ticks on a wild black bull, she would feel an aversion to sexual intercourse.

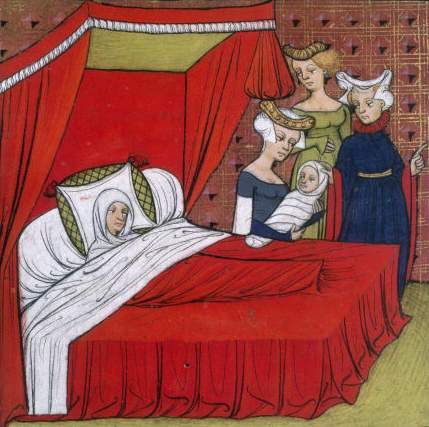

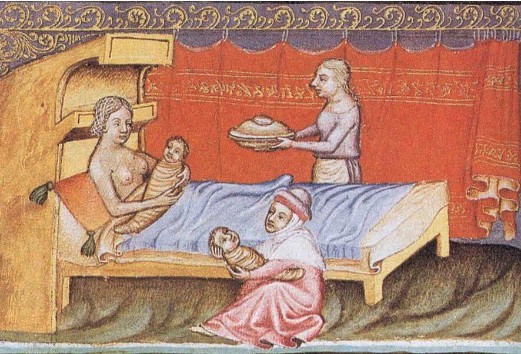

I imagine she would. I do not think that my fourteenth century characters ever found the need for such remedies, certainly not the redoubtable Alice Perrers. All in all a fascinating subject, with many questions, and no clear answers. What we do know is that, although the scenes here from medieval miniatures show a happy outcome, childbirth was an essentially dangerous time for both mother and offspring.