Katherine Swynford

The Iconic 14th Century Love Affair of Katherine, Lady Swynford and John, Duke of Lancaster

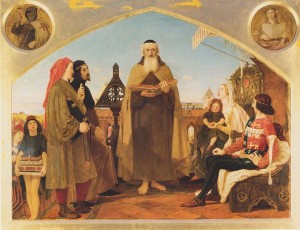

Although there are well documented portraits of John, Duke of Lancaster, known to history as John of Gaunt, one of the sons of Edward III, there are few that can be positively identified as Katherine Swynford, his mistress and ultimately his wife. This is a painting by Ford Madox Brown, one of the nineteenth century pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, showing John Wycliffe reading from his translation of the Bible into English to John of Lancaster. Also in the picture is a woman and child, believed to be a rare depiction of Katherine Swynford and one of their children, probably their eldest son, John Beaufort. The man in the red hood is Geoffrey Chaucer, who was part of the Lancaster household and married to Katherine’s sister Philippa.

I have decided to write the story of Katherine Swynford and John of Lancaster, to be released in Spring 2014. Am I mad to do so? What is it that has made me take on such a sacred subject, to step onto such hallowed ground?

Katherine, that beautiful love story written by Anya Seton, was first published in 1954. It is considered to be a classic novel of its kind, read and adored by all aficionados of historical fiction. I read it in the 1970s and was entranced, carried away by the vivid depth of accurate historical detail and the sheer romance of the relationship. I could not envisage a better historical novel.

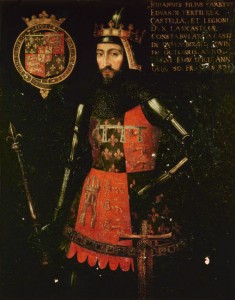

Here, of course, the hero of the hour, John of Lancaster, looking suitably magnificent in what is thougth to be a copy of a contemporary portrait. His tabard depitcts the leopards of England as well as the French fleur de lys and the emblem of Castile of his second wife Constanza.

It has to be said that most colourful historical characters and events in English medieval history have been written and re-written over the years from every possible angle and every point of view. There are only so many suitable female medieval protagonists for a dramatic novel. No point in writing about a woman who is loving and beautiful but does very little between birth and death. Thus the dynamic ones are well subscribed. But Katherine Swynford? No one as far as I am aware has made any attempt to repeat the magnificent story of Katherine and John. So why is that? Is there a belief that the story was so well told at the hands of a master in the first place that it could not be bettered? Most likely that is true.

Beware anyone who attempts a re-telling. It is enough to make a tempted author step carefully in a different direction …

This is the Troilus Frontispiece from Chaucers’s Troilus and Criseyde. The lady in blue, kneeling at the front, second from the left, it is believed may be Katherine. it is a nice thought.

So what made me decide to place my head on the block and write about these most famous of 14th century lovers? Certainly not a desire to do a better job than Ms Seton. I would not presume. But perhaps to write something different. And Katherine Swynford fits so perfectly into my project of medieval wives and mistress, following on from Alice Perrers and Katherine de Valois. As I was writing about Alice, Katherine Swynford crossed my path more than once and, comparing her situation to that of Alice, she intrigued me.

So, now in need of a new project, I felt that I must unpick this splendid pair because it seems to me that the relationship between John and Katherine was far more than just a simple love affair. How could a simple falling in love cause this unlikely couple to cast aside all they knew, accepted, and believed to be morally right:

– Katherine was, based on all evidence, strongly religious. A respectable widow, highly principled, raised under the influence of that remarkable woman Philippa of Hainault who was known for her staunch beliefs, Katherine seems to have been the last woman to cast aside away all morality and slip into a role that would destroy her reputation and bring her under the dire judgement of God.

– John was equally known to hold to strong religious views with a powerful sense of duty and a reputation for high chivalry despite his affairs outside marriage. Chaucer made him immortal as the man in black who worshipped his dead wife Blanche, in The Book of the Duchess.

Yet both Katherine and John were prepared to abandon all moral tenets, all sense of responsibility, all thoughts of God’s grace, when embarking on an affair that lasted on and off for almost 30 years, producing four illegitimate children as evidence of their sin. John was perfectly willing to place Katherine in the ducal household as magistra to Blanche’s daughters – Philippa and Elizabeth – in effect forcing Constanza, his second wife, to accept his mistress. This was deliberately flaunting Katherine under Constaza’s nose, an action that defies most attempts to explain or forgive. Their relationship became increasingly indiscreet, and when discovered the outcry was so great that John was forced to reject Katherine, publicly and terribly. And yet they were to be reunited, John finally marrying Katherine in 1396 a mere three years before he died.

Here is Kenilworth, one of the great Lancastrian castles where the affair between John and Katherine blossomed. But they were equally intimate at Hertford and Tutbury, at Leicester, at Kettlethorpe, Katherine’s own estate in Lincolnshire, and of course at the magnificent Savoy Palace that was destroyed in 1381 during the Peasants’ Revolt. Discretion became less and less a goal for the lovers although they started out with good intentions. Their love affair became quite blatant.

Then was this just a love affair? I think not. I think it was far more powerful, a Grand Passion in effect, difficult, edgy, sometimes uncomfortable for both of them in its demands and overwhelming in its power. Without doubt they had a great need for each other. It forced them to abandon all conscience. Remorseless, relentless, it was not a romance but an emotion beyond their control, driving all before it – morals, responsibilities, duties, all sense of right or wrong. But it must have been exhilarating too, breath-stopping in that it destroyed their will-power to hold apart. It proved to be impossible to escape, even when Katherine might have wished she could, after what she could only see as John’s cruel rejection of her. John was her love, her life, her reason for being, as she was John’s. How did Katherine square this with her staunch belief in God? I’m not sure, but undoubtedly she did.

And so I consider it to be a tale of compulsive desire and need, sweeping all before it with the force of a tsunami, and so much stronger than love. I have to write it. I will be delighted to do so, and my editors are very pleased too.

Here is Katherine’s tomb in Lincoln Cathedral, fitting of course for a Duchess of Lancaster as she ultimately became. It is many years since I visited it. It will demand another journey to the north for me. John was buried next to Blanche, and their tomb was sadly destroyed in the Fire of London.

And those who will undoubtedly say that I should not take on the story of Katherine and John? That my new novel can never hold a candle to Ms Seton’s Katherine? Well, that is their right. As it is mine to re-engage with this wonderful relationship after sixty years. I will enjoy every minute of writing about this unbreakable bond that was capable of bringing as much heartbreak as happiness, and that was to have such an impact on the future history of England.

I have made no attempt to re-read Katherine since I first discovered it in the 1970s. Nor will I. I think it would not be a wise move …