Who was Elizabeth Plantagenet? How did a royal medieval princess come to be buried in the lovely rural church of Burford in Shropshire?

Elizabeth Plantagenet, a Lost Medieval Princess

In July 2012 I posted in English Historical Fiction Authors about the remarkable memorials to the Cornewall family in the lovely church of Burford in Shropshire.

http://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.co.uk/2012/07/buried-treasure.html

And one of the memorials there is to Elizabeth Plantagenet. I was fascinated enough by her to write more about her astonishingly eventful life. Apart from her eye-catching matrimonial adventures, for me there are some interesting historical overlaps. Elizabeth would have known both Katherine Swynford and Alice Perrers, Edward III’s mistress, very well, their paths crossing with great frequency. Here is my post on Elizabeth …

So who was Elizabeth Plantagenet? What we know of parts of her life is fairly superficial, but the details that we do have suggest that she was a headstong, dynamic young woman, and her experiences were far from ordinary, even for a princess.

Elizabeth was the younger daughter of John of Gaunt and the beautiful Blanche of Lancaster. She was born in about 1363 and raised with her elder sister Philippa and younger brother Henry in the magnificent Lancaster residences at Kennilworth, Tutbury, Hertford and of course the Savoy Palace in London – the most luxurious palace in England – which was to be razed to the ground in the Peasant’s Revolt in 1381.

This is the famous portrait of John of Gaunt, thought to be a copy of one taken from life. He was the third son of Edward III, who became Duke of Lancaster through his marriage to Blanche.

After Blanche’s premature death in 1368 and Gaunt’s re-marriage in 1371, Elizabeth and her siblings joined the household of Gaunt’s second wife, Constanza of Castile. The magistra appointed to teach the two girls in these years was of course Katherine Swynford, Gaunt’s long-standing mistress whom he eventually married after Constanza’s death in 1389. It would be enlightening to know Elizabeth’s opinions of her infamous governess. Was her own moral compass in any way influenced by Katherine’s liaison with Duke John? Sadly, we do not know, although Elizabeth’s subsequent love affairs might suggest that she saw little to criticise in her governess’s relations with her father.

In June 1380, a marriage was arranged for Elizabeth: she became the wife of John Hastings, Earl of Pembroke, the ceremony taking place at Kenilworth. Interestingly she was wed before her elder sister who might have been saved for a more important diplomatic marriage to help her father secure the throne of disputed Castile in his wife’s name.

Here is Kenilworth, looking dominant and moodily impressive even in decay.

Elizabeth’s marriage, clearly arranged to cement a valuable English alliance, was doomed. Elizabeth was appoaching maturity at 17 years, a young woman who was intelligent, literate, well read and adept at dancing and singing. Her new husband was a mere child at only 8 years. We can only ponder her thoughts on such an match. Perhaps she treated John as she did her young brother Henry Bolingbroke. Certainly Elizabeth’s marriage to John was never consummated.

Unsuprisingly, given the circumstances, Elizabeth fell in love. The man who took her eye was Sir John Holland, Duke of Exeter, son of Joan of Kent by her first marriage, and so half-brother to King Richard II. He was a man with a reputaion for self-interested scheming but also for considerable presence and charm. He was certainly able to seduce Elizabeth and lured her into his bed. I expect she was not averse to it since her own marriage to her child-husband was so sterile.

So Elizabeth became Exeter’s lover – and scandalously pregnant. To deflect any further scandal, Gaunt arranged a rapid annulment of his daughter’s unconsummated marriage – she was 23 and her husband still only 14 – and Elizabeth was hastily wed to Exeter in June 1386. The marriage proved to be very successful. Exeter was drawn into the family and reconciled with Gaunt. Elizabeth’s first child, the first of 5 they had together, was born early in 1387 and named Constance. As far as we know they were happy together.

Sadly the marriage was not to last into old age. In 1400 a plot was discovered to assassinate the newly crowned King Henry IV, Gaunt’s son Bolingbroke, and restore Richard to the throne. Exeter was found to be involved on the side of his half brother. He was captrued and promptly beheaded, leaving Elizabeth a widow. How did she respond to her brother’s killing of her husband? Did she grieve? Again, we do not know.

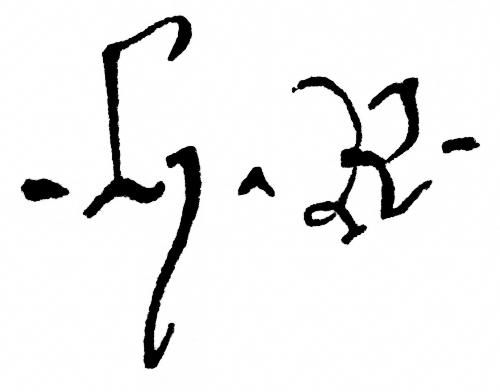

This is Henry IV’s signature, as he often used it on documents. Was this the signature that condemned Exeter to death?

If Elizabeth did grieve for John Holland, it was briefly, for by December of that same year she was remarried to John Cornewall, Baron Fanhope, who had caught her attention at a tournament in York in July. Rumour has it that they had already shared a bed before the marriage was solemnised. Whatever the truth of it, Elizabeth risked royal favour when she failed to get the King’s licence for the marriage. Being a confident woman however she persuaded her brother King Henry to look lightly on her actions. He forgave her and even gave her a dower taken from Exeter’s forfeited estates. Elizabeth and John Cornewall had two children together.

Elizabeth predeceased her husband and died in 1426 and is buried in the church at Burford in Shropshire, a lovely 14th Century church tucked away in the depths of Marcher countryside near Tenbury Wells.

A strikingly painted effigy marks Elizabeth’s tomb in the chancel. The rich red and blue of her garments was probably repainted when the church was given some restoration in the late 19th century but it is still a lovely representation with its gilding, angels and ermine lined cloak. Although Elizabeth was 61 when she died, she is shown here as a young woman and very beautiful.

Elizabeth is accomapnied by other memorials to the Cornwwall family, who were lords of Burford, but not that of Sir John who was buried in Ludgate in London.

To tie up the loose ends of Elizabeth’s story, they are quite tragic. John Hastings, released from his marriage to Elizabeth, married Philippa Mortimer. Before they could settle into married life, he died at the age of 17 in a jousting accident when he was struck in the groin by a lance. It was a terrible and painful end for the young man.

Elizabeth’s daughter with Sir John Cornewall, Constance, married the Earl of Arundel, but died without issue. Their son, another John, was killed at the Siege of Meaux in 1421 when only 18. He was standing next to his father when decaptitated by a gun stone. It is said that Sir John, as a result, never went to war again. I am sure Elizabeth felt his loss keenly.

It seems strange to find a Plantagenet princess buried far from home in Burford. And what an unsettling story it is for Elizabeth, with its mix of happiness and tragedy. I am sure there is a dramatic novel in it. Perhaps one day …